If you thought the origins of additive manufacturing were fairly recent, think again. In 1974, the original series of Star Trek introduced “the replicator”, a device remarkably like a modern 3D printer. It was another 7 years before the first real life version was created. Take a step further back and the story becomes longer and even more interesting.

In this blog I’ll investigate a broader view and argue that additive manufacturing is an example of biomimicry, and as such its origins go back all the way to Leonardo da Vinci whose “Codex on the Flight of Birds” is the first documented example of science copying the natural world.

Additive manufacturing and patterns in nature

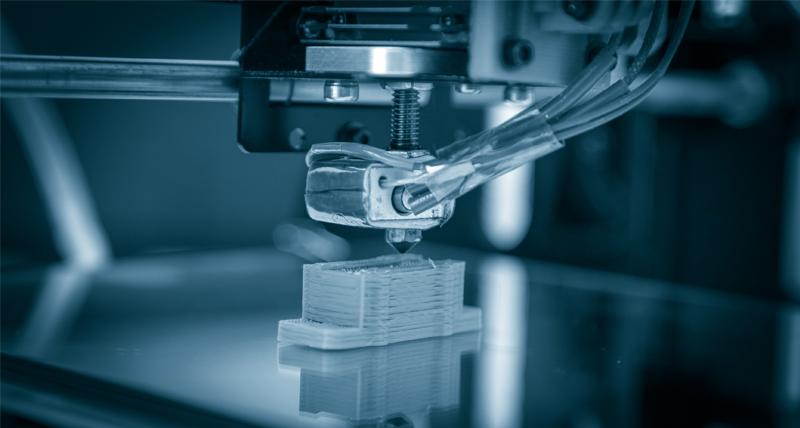

Look at a 3D printed object and you’ll normally notice a series of lines or rings. That’s because additive manufacturing works by depositing layers, one on top of another. Slice a 3D printed object cleanly in half and this phenomenon is even more pronounced. These objects have an internal structure because they are built from the inside out.

That might sound strange but it’s the most natural thing in the world.

Every child knows that you can tell the age of a tree by counting the rings inside it. That’s because trees grow ‘additively’. They have a development cycle where cells divide and create layer upon layer. It’s not just trees, it’s almost everything in the natural world.

Additive construction is used in nature

We might argue that additive manufacturing is as old as the hills, literally. Some geological processes could be described as ‘additive’, think of volcanic islands created by layers of molten rock one on top of the next, or sedimentary rock formations laid down over millions of years.

We could even argue that the stars themselves are made additively. In the vast nebulae of space, particles generate forces of attraction which draw in other particles adding layers and increasing density across inconceivable timeframes.

When you think of it in those terms, it’s hardly surprising that this technology can make almost anything. The possibilities are nearly endless, from the very large through to the very small. These days we’re seeing 3D printed buildings at one end of the spectrum and objects made with carbon nanotube composite ink at the other.

Additive manufacturing – a technology without limits

The limits of additive manufacturing are out there somewhere, but they’ve yet to be reached. Where the limit might be is a frequently asked question. The answer seems to keep changing. A better question would be “what are the limits of additive manufacturing today?”

Pushing the boundaries of 3D printing

We can print geometric shapes with complex freeform curves, mimicking nature. We can print metal, and even objects with moving parts built in. Things that would be difficult to create using traditional extrusion, stamping, casting and molding methods suddenly become easier. We can print brittle materials like glass and ceramics. We can create objects that bend and flex using materials like rubber.

There are even organisations bringing 3D printing into the kitchen. Here the lines between art, science and nature really become blurred. We’ve got chefs using CAD programs and 3D printers to create new pasta shapes that hold a sauce better, offer different textural experiences, or cook more evenly. Imagine taking your partner out for an anniversary meal, ordering the pasta, and out comes a dozen roses served in a deep red tomato sauce.

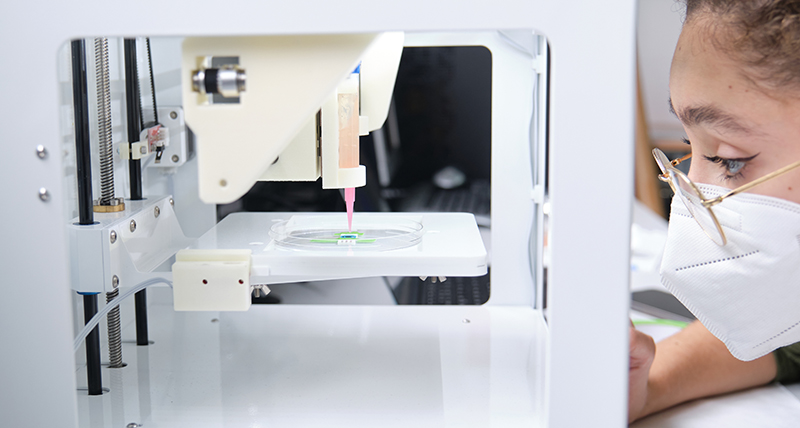

If you think that’s cool, consider the reality of 3D printed biological tissue and the opportunities that presents. The technology is already in use and we can only dream about where it may lead us. It’s science and engineering inspired by natural processes, to then create ‘natural’ objects. There’s something rather poetic about that.

But what do you think? Share this blog with your social networks and join the debate or click here for more information about Hexagon’s additive manufacturing solutions.